Introduction

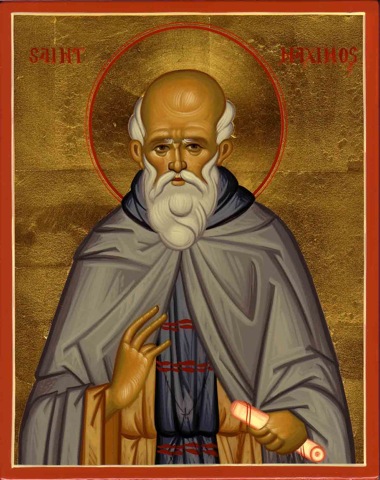

From the Prologue entry for January 21st (Church Calendar):

“Our Holy Father Maximus the Confessor. By birth a citizen of Constantinople and at first a high-ranking courtier at the court of the Emperor Heraclius, he then became a monk and the abbot of a monastery not far from the capital. He was the greatest defender of Orthodoxy against the Monothelite heresy, which developed from the heresy of Eutyches. That is to say: as Eutyches asserted that there is in Christ only one nature, so the Monothelites asserted that there is in Him only one will. Maximus resisted this assertion and found himself in opposition to both the Emperor and the Patriarch. But he was unafraid, and persevered to the end in proving that there are in the Lord two wills and also two natures. By his efforts, one Council in Carthage and one in Rome stood firm, and both these Councils anathematized the Monothelite teaching. Maximus’ sufferings for Orthodoxy cannot be described: he was tortured by hierarchs, spat upon by the mass of the people, beaten by soldiers, persecuted, imprisoned; until finally, with his tongue cut out and one hand cut off, he was condemned to exile for life in Skhimaris, where he gave his soul into God’s hands in the year 662. Even with his tongue cut out, he was, through God’s grace, able to speak even more clearly in defense of the Faith.”

Saint Maximos’ stand against widespread heresy, particularly among those calling themselves Orthodox, truly makes him a Saint for today. This is illustrated from the following excerpt of a conversation that took place between two Byzantine envoys, Troilos and Sergios, and Saint Maximos—as recorded in the January volume of the Great Synaxaristes (pp. 857-858)—during the period of his interrogations prior to his last exile and death :

… Troilos and Sergios then posed another question: “Then we are to understand that thou wilt not enter into communion with the throne of Constantinople?” Father Maximos replied, “I will not commune.” They inquired further, asking, “For what reason wilt thou not commune with the patriarchate?” Father Maximos answered them with a serious countenance, saying with a sigh, “On the one hand, there is nothing more onerous than the reproach of one’s conscience; but, on the other hand, there is nothing more desirable than the approval of one’s conscience.” They pressed the holy man to give them an answer for his lack of communion with them. Father Maximos then explained: “I cannot enter into communion with the throne of Constantinople, because the leaders of that patriarchate have rejected the resolutions of the four œcumenical synods. Instead, as their rule, they have accepted the Alexandrian Nine Chapters. Thereafter, they accepted the Ekthesis of Patriarch Sergios and then the Typos, which rejects everything that was proclaimed in the Ekthesis, thereby excommunicating themselves many times over. Together with having excommunicated themselves, they have been deposed and deprived of the priesthood at the Lateran Council held in Rome. What Mysteries can such persons perform? What spirit comes upon what they celebrate or those ordained by them?” The saint’s visitors then asked, “Then thou alone wilt be saved, while everyone else perishes?” Father Maximos said, “When Nebuchadnezzar made a golden image in the province of Babylon, he summoned all those in authority to come to the dedication of the image [Dan. 3:1, 2]. The holy Three Children condemned no one. They did not concern themselves with the practices of others, but looked only to their own business, lest they should fall away from true piety. When Daniel was cast into the lions’ den, he did not condemn those who prayed not to God that they might obey the decree of Darius [Dan. 6:12 ff.]. Instead, he concentrated on his own duty. He preferred to die than to sin against his conscience and transgress God’s law. God forbid that I should judge or condemn anyone or that I should claim that I alone shall be saved! I should much prefer to die than to betray the Faith in any way or go against my conscience. … Were the universe to enter into communion with the patriarch, I should never commune with him. Take heed of the words of the Holy Spirit through the apostle: ‘Even if we, or an angel from out of heaven, should preach a gospel to you besides what Gospel we preached to you, let such a one be anathema [Gal. 1:8].'” The envoys then asked, “Is it truly needful to confess two wills and operations in Christ?” Father Maximos replied, “It is absolutely needful, if we are to remain Orthodox in doctrine. … Though I do not wish to grieve our dutiful emperor who is a good man, yet I fear God’s judgment by keeping silence about those things which God commands us to confess. …”

For those wishing to learn more of Saint Maximos, it is highly recommended that the complete entry found in the Great Synaxaristes be read. If this is not available to you (or while you are obtaining a copy), a somewhat interpretive history is provided below. A Background section provides a framework of the politics, religious issues and war that surrounded Saint Maximos. This is followed by a Chronology section that provides a blended, summary outline of events in Saint Maximos’ life (“blended” in the sense that many dates are inferred differently by different authors where precise records were not kept). As Saint Maximos was a theologian who built on the foundation left by, e.g., Saint Dionysios the Areopagite and Saint Gregory the Theologian, and who was built on, in turn, by, e.g., Saint Symeon the New Theologian and Saint Gregory Palamas, a listing of writings is available in the third section entitled Saint Maximos’ Works (both the original Greek and available English translations are given). The last section is a Bibliography of those sources used in drafting this article.

Background

Where Truth exists, heresies abound. One “family” of heresies of particular interest in the life of Saint Maximos as combatant is the set of twisted doctrines concerning the nature of Christ—the origin of which is generally attributed to Eutyches ca. 447 A.D.—that is generally referred to as monophysitism (“one nature”). This heresy spread quickly and was widely adhered to across the Roman Praetorian Prefecture of the East (roughly speaking, think the land areas of modern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Egypt, and Libya; Orient herein) and beyond. The Fourth Œcumenical Council (the Council of Chalcedon) held in 451 resolutely condemned the monophysites, and in the Fifth Session declared in Truth:

“Following, therefore, the holy fathers, we all in harmony teach confession of one and the same Son our Lord Jesus Christ, the same perfect in Godhead and the same perfect in manhood, truly God and the same truly man, of a rational soul and body, consubstantial with the Father in respect of the Godhead, and the same consubstantial with us in respect of the manhood, like us in all things apart from sin, begotten from the Father before the ages in respect of the Godhead, and the same in the last days for us and for our salvation from the Virgin Mary the Theotokos in respect of the manhood, one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten, acknowledged in two natures without confusion, change, division, or separation (the difference of the natures being in no way destroyed by the union, but rather the distinctive character of each nature being preserved and coming together into one person and one hypostasis), not parted or divided into two persons, but one and the same Son, Only-begotten, God, Word, Lord, Jesus Christ, even as the prophets from of old and Jesus Christ himself taught us about him and the symbol of the fathers has handed down to us.”

Yet in spite of the pronouncements of the Council, the heresy remained and continued to spew its poison (down to the present, in fact, in the various branches of the Oriental “orthodox” church: the Armenians, Copts, Ethiopians, Eritreans, and Syrians). At times it changed its cloak in hundreds of various hues so as to further spread its deception, including monoenergism (aka monenergism, one energy; think activity or operation) and monothelitism (one will).

Another deeply rooted family of heretical ideas that Saint Maximos fought is found hiding in the prolific and often (unfortunately) praised works of Origen (died ca. 254). The first Origenist crisis arose in the second half of the 4th century among the monks in Nitria, Egypt, and gradually invaded the monasteries of Palestine where it was combatted by St. Epiphanius, Bishop of Salamis. In the 6th century, Origenism again rose its ugly head to an alarming degree, and again among Palestinian monks. Prior to the formal opening of the Fifth Œcumenical Council (the Second Council of Constantinople) held in 553 A.D.—at the request of the Emperor Justinian—the bishops who had assembled investigated and then issued a condemnation of Origenism in the form of 15 canons (anathemas) aimed at specific heretical ideas. In the Eighth Session of the Fifth Council itself, 14 canons (anathemas) were also promulgated, one of which included a condemnation of Origen himself (along with other heretics):

“11. If anyone does not anathematize Arius, Eunomius, Macedonius, Apollinarius, Nestorius, Eutyches and Origen, with their impious writings, and all the other heretics condemned and anathematized by the holy catholic and apostolic church and by the aforesaid holy four councils, and those who held or hold tenets like those of the aforesaid heretics and persisted {or persist} in the same impiety till death, let him be anathema.” [emphasis added]

Like other heresies that, once birthed, never die, the works of Origen are still with us in readily accessible forms; even worse, he is usually ranked among the “church fathers” with no indication to the uninformed reader that subtle heresies are lurking in the text.

God is patient and long-suffering (Ps. 85:15). However, the “salt” of the Orient had lost its savor (Luke 14:34). Like the Jews, they rejected the “prophets” of the synods and faithful fathers (cf. 1Th. 2:15). And so God gave them up to uncleanness (Rom. 1:18-32) and let the heathen rule over them (cf. Joel 2:17), giving them a chance to repent and return to Him.

In 611 the Persians conquered Syria, occupying Antioch and Damascus, and then moved on to Palestine where they pillaged Jerusalem in 614—that holiest of relics, the True Cross, was taken, and numerous prisoners including the Patriarch of Jerusalem, Zacharias, were sent to Persia.

With the imminent invasion of Egypt, the Roman Emperor Heraclius attempted to shore up imperial authority in what was remaining of the Orient. In 616, Heraclius and the patriarch (of Constantinople) Sergius saw monoenergism as a way to use religion for political purposes—that is, by restoring ecclesiastical unity (through heresy!), he might regain the people’s will to fight the invaders; so, with the introduction of said new heresy, Heraclius’ cousin Nicetas was able to negotiate a tentative union between the (already heretical) Syrian Jacobite and Egyptian Coptic churches.

A Persian army crossed Asia Minor, conquered Chalcedon in 616, and encamped near Chrysopolis (just across the Bosporus from Constantinople), while another conquered Egypt, with Alexandria falling in 618 or 619. The Balkans also came under the threat of the Avars, with Thessalonica, Greece, held under siege from 617 to 619.

Circa 620, Heraclius stripped the churches of both the capital (Constantinople) and provinces of gold and silver, bought peace with the Avars in the Balkans, and funded an army with which to begin a war with Persia. In all, Heraclius quite successfully conducted three Persian campaigns between the years 622 and 628, reclaimed all the lands lost, took for himself the Persian title “King of Kings”, and forged a monoenergistic union with the Nestorian catholicos of Persia (who rejected not only the 4th Œcumenical Council, but the 3rd as well!) that was sealed by eucharistic communion.

But the people did not return to the Truth. Their behavior paralleled many stories in the Old Testament concerning the Israelites and, later, the Jews. For example:

“For thus saith the Lord, Shall not he that falls arise? or he that turns away, shall he not turn back again? Wherefore has this my people turned away with a shameless revolting, and strengthened themselves in their willfulness, and refused to return? Hearken, I pray you, and hear: will they not speak thus, There is no man that repents of his wickedness, saying, What have I done? the runner has failed from his course, as a tired horse in his neighing. Yea, the stork in the heaven knows her time, also the turtle-dove and wild swallow; the sparrows observe the times of their coming in; but this my people knows not the judgments of the Lord.” (Jeremias 8:4-7 Brenton LXX)

The monenergist agenda continued to be pushed; the heretical Armenian church was reunited in 630 (Heraclius shared in communion with the monophysite catholicos of Armenia), some measure of reunion was achieved in the churches of Syria and Mesopotamia, and great success was enjoyed in Egypt under the monenergist convert Cyrus, patriarch of Alexandria in 633 (the Pact of Union). When Saint Sophronios (commemorated 11 March; consecrated Patriarch of Jerusalem in 634) objected to the work of Cyrus, patriarch Sergius forbade further discussion of one or two activities in Christ (the Psephos); after his consecration, Saint Sophronios declared his support for Chalcedon, and rejected monenergism on the grounds that it entails monophysitism. (As an aside, the Sixth Œcumenical Council had this to say of his letter (Hefele, p. 167): “We have also examined the synodal letter of Sophronius, and have found it in accordance with the true faith and the apostolic and patristic doctrines. Therefore we received it as useful to the Catholic and apostolic Church, and decreed that his name should be put upon the diptychs of the holy Church.”)

Following the death of Muhammad (632 A.D.), in 633 Muslim forces began invading the eastern territories of the Roman Empire (Byzantium). Damascus fell in 635. Jerusalem was surrendered by Patriarch Sophronios in 637.

In 638 Heraclius published the Ekthesis, a work of Sergius and Pyrrhus (Sergius’ successor), that established monothelitism as the official doctrine. Several months after Heraclius died in 641, one of his grandsons, Constans II, became sole emperor.

Alexandria fell to Muslim forces in 642.

Like Heraclius, Constans tried to control the religion of his empire for political purposes; in 648 he issued what is known as the Typos—an imperial edict that made it illegal to discuss in any manner the topic of Christ possessing either one or two wills, or one or two energies (in effect, protecting the Ekthesis).

By the year 650 Syria, a part of Asia Minor and Upper Mesopotamia, Palestine, Egypt, and part of the Byzantine provinces in North Africa were under the sway of the Muslims.

Constans II vigorously persecuted anyone who spoke out against monothelitism, including Pope Martin I (arrested 653, died 655) and our Saint Maximos (arrested 653, died 662). (Pope Martin I is commemorated as a Hieromartyr, along with the holy and righteous and confessing Bishops of the West who suffered with him on 13 April—or 14 April in the Slavonic Calendar—and on 20 September when he is jointly celebrated with Saint Maximos.)

In 654, Muslim sea forces plundered Rhodes. In 655, at the Battle of the Masts, 500 Byzantine ships were destroyed and the emperor was almost killed. In 660 Armenia was taken.

Without dwelling further on Constans II, his life can be summed up by his death: he was assassinated in his bath in 668.

The Sixth Œcumenical Council (the Third Council of Constantinople) was held in 680-681 A.D., at the request of the holy and right-believing Saint Constantine the New (Emperor Constantine IV; commemorated 03 September), to investigate monothelitism. The summary decision of the fathers is recorded in the acts of the Eighteenth Session (Hefele, pp. 149-178):

“… Following the five holy and Œcumenical Synods and the Fathers of repute, and confessing that our Lord Jesus Christ, one of the Holy Trinity, is perfect in the Godhead and perfect in the manhood, … [the creed of Chalcedon followed here]. We also declare that there are two natural wills and two natural energies in Christ, according to the teaching of the holy Fathers. And the two natural wills are not opposed to each other—God forbid—as the impious heretics said, but His human will followed, and it does not resist and oppose, but rather is subject to the divine and almighty will. … Therefore we confess also two natural wills and operations (energies) going together harmoniously for the salvation of the human race. A different faith no one may proclaim or hold; and those who venture to do so, … or will introduce a new formula for the destruction of our definition of the faith, shall, if bishops or clerics, be deposed from their clerical office, but if monks or laymen, shall be anathematized. … Therefore we punish with excommunication and anathema Theodore of Pharan, Sergius, Paul, Pyrrhus, and Peter, also Cyrus, and with them Honorius, formerly Pope of Rome, as he followed them, but especially Macarius and Stephen, … also Polychronius, …”

Saints Martin and Maximos and those with them were vindicated!

Chronology

The Monk Maximos (aka Maximus) the Confessor (Μαξίμου του Ομολογητού, Преподобный Максим Исповедник) was born in Constantinople in 580 A.D. and given the name Moschos at his baptism. In his youth he received an extensive education that enabled him to enter government service, where through competence he rose to serve as first secretary or head of the Imperial Chancellery (secretariat) on the ascension of the Roman (Byzantine) emperor Herakleios to the throne (Heraclius; reigned 610-641).

After several years as protosecretary, ca. 613-614, Moschos retreated to the Monastery of the Theotokos at Scutari (Chrysopolis in Bithynia, modern Üsküdar, Turkey) to take up the practice of hesychasm or “stillness” (for more see The Orthodox Prayer Rope), and which is where he was tonsured a monk with the name Maximos. While it is certainly understandable that someone would want stillness after even a short time at court, we can speculate that St. Maximos was responding to some soul searching that went on following the cataclysmic events of the day: the beginning of the Persian wars.

Circa 624 or 625, although no source provides a reason, Saint Maximos and his first disciple Anastasios eventually decided to leave Chrysopolis for the monastery of Saint George at Kyzikos (Cyzicus, now Erdek, Turkey); however, with the occupying Persians in Chrysopolis—with all the burden that that meant to the local populace (to put it mildly)—it is no small wonder that the hesychasts left!

In 626 the Avaro-Slavonic hordes besieged Constantinople and the Persians sent part of their army to Chalcedon. The renewed tensions and fighting in the area again sent Saint Maximos and his disciple into flight, this time much further afield. Based on his correspondence it is possible that Saint Maximos visited Cyprus. He also visited Crete where the Severian bishops held a dispute with him (they professed “one will” in Christ).

Circa 628-630 Saint Maximos arrived at the monastery called Eucratas in proconsular Africa near Carthage. There he met his new spiritual teacher and abbas Saint Sophronios, who guided Saint Maximos in his studies on the Chalcedonian doctrine and awakened in him a sense of the danger in the new heresy of monothelitism.

Following the Syriac life of Saint Maximos, at some point during the 630s he went to Syria-Palestine where he was active shortly after the Muslim conquest. Somewhat speculatively, it can be reasoned that Saint Maximos followed his abba, Saint Sophronios, to Palestine upon his consecration as Patriarch of Jerusalem in 634.

In the latter part of 641, the year of the accession of Constans II to the throne, Saint Maximos returned to Africa. Possible reasons would seem to include both the oppression that developed under Muslim rule as well as—with the publication of the Ekthesis—emboldened heretics in the East; life in Roman Africa would both be quieter from heretics, if you will, of two types: muslims and monophysites.

In 645 Saint Maximos had a disputation with Pyrrhus over monothelitism, a deposed and exiled “patriarch” of Constantinople. Pyrrhus had succeeded Sergius, but was accused of plotting against the emperor. After the disputation he publicly acknowledged his error and wrote a book of his confession of faith. Saint Maximos travelled with Pyrrhus to Rome in 646 to place his written anathema against monothelitism on the tomb of the apostles. (Pyrrhus, by virtue of his Orthodox confession, was received by Pope Theodore as Patriarch. However, in 647 he subsequently returned to Constantinople and re-embraced monothelitism. In 654, for ~6 months before his death, he was restored to his throne.)

Constans II asked Pope Martin, Theodore’s successor, to approve the Typos, but he refused saying, “If the entire world should embrace the new heresy, I would not. I will never renounce the doctrines of the Gospels and the apostles, nor the traditions of the holy fathers, even if I am threatened with execution.” In 649, Pope Martin I also assembled a council of 106 bishops in the Lateran Palace where both the Ekthesis and the Typos were condemned as heretical pieces of work, excommunicated the then patriarch of Constantinople, Paul, and issued a letter to Constans that blamed the patriarch for endorsing monotheletism; Saint Maximos was present. Constans II, considering opposition to the Typos as treasonous, issued orders for the arrest of Pope Martin and Saint Maximos (others who stood with the Lateran council were persecuted as well). In 653 the arrest orders were finally carried out with the help of an army, and both Saints were taken to Constantinople. Circa 653-655 Saint Maximos was very harsly treated, finally ending up in exile in Bizye, Thrace (present day Turkey). Saint Martin died in 655 of starvation while in exile in Cherson in the Crimea.

In 656 “Patriarch” Peter, Pyrrhus’ successor, and Constans II, tried unsuccessfully to tempt Saint Maximos into communion, and sent several envoys to him at Bizye. He was then returned to Constantinople for a second examination, following which he ended up exiled to Perveris (Perberis), Thrace.

Several years later, in 662 (some sources 659), Saint Maximos was recalled to Constantinople and subjected to a third examination. He and his life-long disciple Anastasius are exiled with their tongues and right hands cut off. Saint Maximos was sent a last time in exile to the Schemarion (Schiomaris, Tsikhe-Muris) fortress at Lazica, near present day Tsageri, Georgia, not far from the Black Sea. There he died on the 21st day of January, in the year 662, at the age of eighty-two. After he was buried, miraculously there appeared three lamps over his tomb by night that illuminated the entire place.

Saint Maximos pray to God for us, that we may always remain faithful to the Truth!

Saint Maximos’ Works

In Greek

The Greek texts written by Saint Maximos, or directly related to his work (e.g., his disputations) or trials is to be found in two collections:

- Patrologia cursus completus, series graeca (Paris: J.P. Migne, 1857-1904)

- Corpus Christianorum, ser. graeca (Turnhout: Brepols, 1977ff.)

Using the abbreviations PG and CCSG for these two sources respectively, the following list provides a comprehensive list of what is known of the works of Saint Maximos (from Törönen):

- Ambiguorum liber (Ambig. Thom. 1-5) CCSG 48, 3-34; (Ambig. Ioh. 6-71) PG 91, 1061-417

- Opusculum de anima, PG 91, 353-61

- Liber asceticus, CCSG 40

- Capita x [= Diversa capita I, 16-25], PG 90, 1185-9

- Capita xv [= Diversa capita I ,1-15], PG 90, 1177-85

- Capitum theologicorum et oeconomicorum duae centuriae, PG 90, 1084-173

- Capita de caritate quattuor centuriae, PG 90, 960-1073

- Disputatio Bizyae cum Theodosio, CCSG 39, 73-151

- Epistulae (1-45), PG 91, 361-650

- Epistula ad Anastasium monachum, CCSG 39,161-3

- Epistula secunda ad Thomam, CCSG 48, 37-49

- Expositio in Psalmum lix, CCSG 23, 3-22

- Mystagogia, Soteropoulos 1993 [= PG 91, 657-717]

- Opuscula theologica et polemica (1-27), PG 91, 9-285

- Expositio orationis dominicae, CCSG 23, 27-73

- Disputatio cum Pyrrho, PG 91, 288-353

- Quaestiones et dubia, CCSG 10

- Quaestiones ad Thalassium, CCSG 7 and 22

- Quaestiones ad Theopemptum, PG 90, 1393-1400

- Relatio motionis, CCSG 39, 13-51

In Old Georgian

The Life of the Virgin, originally written in Greek, is now only extant in Old Georgian. (It has been translated into English and published in 2012, as set forth below.)

In English (by year of publication)

- Hefele, Charles J., A History of the Councils of the Church, from the Original Documents, Vol. V, Clark, Edinburgh, 1896.

- Disputatio cum Pyrrho (“Abbot Maximos and his Disputation with Pyrrhus”)

- St. Maximus the Confessor: The Ascetic Life, the Four Centuries on Charity. Trans. Polycarp Sherwood. Ancient Christian Writers 21. New York: Newman, 1955.

- Liber asceticus (The Ascetic Life)

- Capita de caritate quattuor centuriae (Four Hundred Chapters on Love)

- The Philokalia. Vol. 2. Trans. and ed. Palmer, Sherrard, and Ware. London: Faber and Faber, 1981.

- Epistulæ (“Various Texts” i.26-47 are extracts from Saint Maximos’ Letters)

- Capita de caritate quattuor centuriae (Four Hundred Chapters on Love)

- Expositio orationis dominicae (On the Lord’s Prayer)

- Ambiguorum liber (“Various Texts” v.62-100 are taken from the Ambigua along with some extracts from St. Dionysios the Areopagite)

- Quaestiones ad Thalassium (“Various Texts” i.48-v.61 are taken from the Questions along with commentary)

- Captia Theologiæ et Œconomiæ (“Two Hundred Texts on Theology…”)

- The Church, the Liturgy, and the Soul of Man: The Mystagogia of St. Maximus the Confessor. Trans. Dom Julian Stead. Still River, MA: St. Bede’s Publications, 1982.

- Mystagogia

- Maximus the Confessor: Selected Writings. Trans. G. Berthold. Classics of Western Spirituality. New York: Paulist, 1985.

- Capita de caritate quattuor centuriae (Four Hundred Chapters on Love)

- Expositio orationis dominicae (On the Lord’s Prayer)

- Mystagogia

- Captia Theologiæ et Œconomiæ (“Chapters on Knowledge”)

- Louth, Andrew, Maximus the Confessor. Early Church Fathers. New York: Routledge, 1996.

- Epistulæ (No. 2, “On Love”)

- Opuscula theologica et polemica (No.s 3 & 7)

- Ambiguorum liber (No.s 1, 5, 10, 41, and 71)

- Maximus the Confessor and his Companions: Documents from Exile. Trans. and ed. P. Allen and B. Neil. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Epistula ad Anastasium monachum (Letter “to Anastasius the monk”)

- Relatio motionis (An eyewitness account of the events of the trial of Maximos and his disciple Anastasius in Constantinople in 655.)

- Disputatio Bizyae cum Theodosio (“Dispute between Maximus and Theodosius, Bishop of Cæsaria Bithynia.” A word-for-word account of the debate between Saint Maximos and Bishop Theodosius, which took place during his exile in Bizya.)

- On the Cosmic Mystery of Jesus Christ: Selected Writings from St. Maximus the Confessor. Trans. P. Blowers. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary, 2003.

- Opuscula theologica et polemica (No. 6)

- Ambiguorum liber (No.s 7, 8 and 42)

- Quaestiones ad Thalassium (Ch. 1, 2, 6, 17, 21, 22, 42, 60, 61, and 64)

- St. Maximus the Confessor’s Questions and Doubts. Trans. D. Prassas. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2010.

- Quæstiones et Dubia

- The Life of the Virgin. Trans. S. Shoemaker. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

- On the Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua, in two volumes. Trans. N. Constas. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Ambiguorum liber (No.s 1-71)

Other translations into English of ancient texts of interest here:

- The Greek Vita (Life) of Saint Maximos is found in the Great Synaxaristes… (January volume, pp. 819-866; see Bibliography).

- The Syriac Vita of Saint Maximos—for careful use, having apparently been written by a monophysite opponent—is the Syriac Vita: “An Early Syriac Life of Maximus the Confessor.” Analecta Bollandiana 91 (1973): 299-346.

Bibliography (by year of publication)

In addition to the texts reference above, the following books were consulted:

Vasiliev, A. A., History of the Byzantine Empire, Vol. 1, University of Wisconsin Press, 1952.

Velimorovic, Bishop Nikolai, The Prologue from Ochrid: Lives of the Saints and Homilies for Every Day in the Year, 4 vols., Mother Maria, trans., Lazarica Press, Birmingham, UK, 1985-1986.

Maximus the Confessor and his Companions: Documents from Exile, P. Allen and B. Neil, trans., Oxford University Press, 2002.

The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon, 2 vols., R. Price and M. Gaddis, trans., Liverpool University Press, 2005, vol. 2 p. 204.

Törönen, Melchisedec, Union and Distinction in the Thought of St Maximus the Confessor, Oxford Early Christian Studies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2007.

The Acts of the Council of Constantinople of 553, 2 vols., R. Price, trans., Liverpool University Press, 2009, vol. 2 pp. 123-124, 270-286.

The Great Synaxaristes of the Orthodox Church, 14 vols., Holy Apostles Convent, Buena Vista, CO, 2002-2010.